Why We Love Pancakes: A Breakfast Favorite Around the World

There’s something universally comforting about a stack of warm, fluffy pancakes. Whether it’s a cozy weekend breakfast with family, a leisurely brunch with friends, or a quick solo treat, pancakes have a special way of bringing people together.

What makes pancakes so beloved is their incredible versatility. You can make them sweet or savory, thick or thin, traditional or wildly creative. From a simple drizzle of maple syrup to extravagant toppings like whipped cream, fruits, and even bacon, pancakes are a blank canvas for culinary creativity.

Around the world, every culture seems to have its own version of pancakes — a beautiful reminder of how food connects us across borders. Whether it’s French crêpes, Russian blini, Japanese soufflé pancakes, or classic American stacks, pancakes are a global comfort food that transcends age, background, and tradition.

The Sweet and Surprising History of Pancakes

Believe it or not, pancakes are one of the oldest forms of cooked food known to humanity! Archaeological evidence shows that as far back as 30,000 years ago, prehistoric humans were grinding grains and cooking them into primitive pancake-like foods on hot stones.

The idea of mixing flour, eggs, and milk to make a batter and cook it over heat has appeared independently in many different civilizations. Ancient Greeks and Romans enjoyed a version of pancakes sweetened with honey. In medieval Europe, pancakes evolved into both savory and sweet forms depending on available ingredients and local traditions.

In America, pancakes took on their now-famous form with the introduction of baking powder in the 19th century, creating that signature fluffy texture we all love today. And let’s not forget Shrove Tuesday — also known as Pancake Day — a holiday rooted in Christian tradition where people would use up rich ingredients like eggs and butter before Lent by making pancakes.

From ancient hearths to modern brunch tables, pancakes have had an incredible journey — and they continue to evolve with every generation of home cooks and professional chefs alike.

The Best Classic Pancake Recipe You’ll Ever Make

There’s a reason why I always come back to this classic pancake recipe — it’s simple, it’s reliable, and it tastes absolutely incredible. These pancakes are fluffy inside, slightly crispy at the edges, and just the right amount of sweet. Perfect for beginners and still satisfying for seasoned cooks.

Essential Ingredients for Fluffy, Golden Pancakes

For 8–10 medium pancakes you will need:

- All-purpose flour – 200g (1 ½ cups), sifted

- Baking powder – 2 ½ teaspoons (10g)

- Granulated sugar – 2 tablespoons (25g)

- Salt – ¼ teaspoon (1.5g)

- Whole milk – 300ml (1 ¼ cups), at room temperature

- Large egg – 1 (about 60g), at room temperature

- Unsalted butter – 30g (2 tablespoons), melted and cooled

- Vanilla extract – 1 teaspoon (5ml)

- Butter or oil – for greasing the pan

Note: Always use room temperature ingredients. Cold milk or eggs can cause uneven cooking and denser pancakes.

Step-by-Step Pancake Perfection: From Batter to Plate

- Mix dry ingredients:

In a large bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, sugar, and salt. Make sure the baking powder is evenly distributed — this guarantees even rising. - Mix wet ingredients:

In a separate bowl, whisk the milk, egg, melted butter, and vanilla extract until fully blended. - Combine gently:

Pour the wet ingredients into the bowl with the dry. Stir with a rubber spatula or wooden spoon until just combined. Small lumps in the batter are completely fine — don’t overmix. - Rest the batter:

Let the batter sit at room temperature for 10 minutes. This short rest allows the gluten to relax and the baking powder to activate, leading to fluffier pancakes. - Heat the pan:

Set a non-stick skillet or griddle over medium heat (around 175°C or 350°F). Lightly grease it with a small amount of butter or oil. - Cook the pancakes:

Pour about 60ml (¼ cup) of batter per pancake into the pan. Cook for 2–3 minutes, until bubbles form on the surface and the edges start to look dry. - Flip and finish:

Carefully flip the pancake and cook for another 1–2 minutes, until golden brown on the other side. Remove and repeat with the remaining batter, greasing the pan lightly if needed.

Mixing Pancake Batter Without Ruining It

Overmixing pancake batter is the number one mistake I see beginners make.

Here’s what you need to remember: Mix the batter just until you don’t see dry flour anymore — and then stop.

The goal is to hydrate the flour, not to develop the gluten like you would in bread. A few lumps in the batter are not just okay, they’re a sign you’re doing it right. Overmixed batter leads to flat, rubbery pancakes instead of light, airy stacks.

Quick tip:

When combining wet and dry ingredients, use a gentle folding motion, scooping from the bottom and turning over the mixture slowly.

Mastering the Flip: How to Cook Pancakes Like a Pro

The perfect pancake flip is all about timing and confidence.

- Wait for the signs: When you see bubbles forming and popping across the surface, and the edges of the pancake look slightly dry, it’s time to flip. This usually takes 2–3 minutes.

- Use the right tool: A thin, wide spatula makes a big difference. Slide it fully under the pancake so it’s well-supported.

- Flip smoothly: In one quick, confident motion, flip the pancake over. Don’t hesitate or jerk your hand — that’s how pancakes fold or tear.

- Don’t press after flipping: Let the second side cook naturally for 1–2 minutes until golden. Pressing down squeezes out the air that makes pancakes fluffy.

Personal experience:

The first pancake is often a “test pancake.” Use it to adjust your heat and timing — then the rest will turn out beautifully.

7 Secrets for Making Your Pancakes Extra Fluffy

Getting that perfect cloud-like texture isn’t just luck — it’s a combination of smart techniques and a few small details that make a huge difference.

Here are my personal 7 secrets to pancake fluffiness:

1. Use Fresh Baking Powder

Baking powder is what gives your pancakes their lift.

Always check the expiration date — old baking powder loses its power. For best results, replace your baking powder every 6 months after opening.

Quick test:

Mix 1 teaspoon of baking powder with a little hot water. If it bubbles immediately and strongly, it’s good to use.

2. Don’t Overmix the Batter

This is crucial: stir only until no dry flour remains.

A few small lumps are exactly what you want. Overmixing activates gluten, which creates chewy, flat pancakes instead of soft, airy ones.

Golden rule:

Mix for about 10–15 gentle folds with a spatula — no more.

3. Let the Batter Rest

After mixing, let your batter sit at room temperature for 10–15 minutes.

This allows the gluten to relax and gives the baking powder time to start working.

The result? Pancakes that are tender inside and fluffy throughout.

Chef’s habit:

I always use this rest time to heat the pan properly. Never rush it.

4. Use Buttermilk or a Buttermilk Substitute

Buttermilk adds a slight tang and reacts with baking powder to create more rise.

If you don’t have real buttermilk, make an easy substitute:

- Add 1 tablespoon (15ml) of lemon juice or vinegar to 300ml of milk. Let it sit for 5 minutes — it will curdle slightly and work just like buttermilk.

5. Preheat the Pan to the Right Temperature

Medium heat is key. If the pan is too hot, pancakes burn outside before cooking through.

I aim for around 175°C (350°F).

If you sprinkle a few drops of water on the pan and they dance and evaporate within 2–3 seconds, you’re good to go.

Tip:

First pancake is always a test. Adjust the heat slightly up or down depending on how it cooks.

6. Don’t Press the Pancakes While Cooking

It’s tempting to flatten them with the spatula — but resist!

Pressing forces out the air bubbles that make pancakes light and fluffy. After flipping, just let them cook naturally without touching.

7. Separate and Whip the Egg Whites (Advanced Tip)

If you want extra-extra fluffy pancakes, try this:

- Separate the egg.

- Mix the yolk into the wet ingredients.

- Beat the egg white until soft peaks form.

- Gently fold the whipped egg white into the batter at the very end.

This technique traps even more air, creating pancakes that are almost soufflé-like in texture.

Personal tip from my kitchen:

“When I want to impress guests with towering pancakes, I always whip the egg whites. Takes a few extra minutes, but it’s 100% worth it for the wow factor.”

Delicious Pancake Variations You Have to Try

Once you’ve mastered the classic pancake, the real fun begins — exploring different styles and flavors. Over the years, I’ve experimented with dozens of variations, and these four have truly become my favorites.

Let’s dive into some seriously delicious options that are guaranteed to impress.

Buttermilk Pancakes That Melt in Your Mouth

If you think classic pancakes are good, wait until you try them with buttermilk.

Buttermilk adds a slight tang and a softer, richer crumb that makes every bite just melt away.

Here’s what you need to tweak the classic recipe:

- Use buttermilk instead of regular milk: 300ml (1 ¼ cups) buttermilk

- Add a bit more baking powder: 3 teaspoons (12g) instead of 2 ½

- Optional: Add ½ teaspoon baking soda for even more tenderness

Preparation tips:

- Follow the exact same steps as the classic recipe.

- Batter will be slightly thicker — that’s perfect.

- Cook at slightly lower heat (about 165–170°C / 330–340°F) to allow the thicker batter to cook through without burning.

Personal note:

Whenever I’m making pancakes for a special brunch, I go for buttermilk. They’re fluffier, more flavorful, and people always ask for seconds.

Japanese Soufflé Pancakes: How to Get That Signature Jiggle

Japanese soufflé pancakes are tall, pillowy, and famously jiggly — and yes, you can make them at home with a little patience!

Special ingredients:

- Same classic ingredients, but separate the eggs.

- You’ll need 2 large eggs (instead of 1).

- Extra fine sugar (caster sugar) works better here for a smoother texture.

Technique:

- Separate the egg whites and yolks.

- Whisk yolks with milk, vanilla, and dry ingredients.

- Whip egg whites with 2 tablespoons of sugar until soft peaks form.

- Gently fold the meringue into the batter.

- Cook low and slow with a ring mold — about 5–6 cm tall.

- Cover the pan with a lid while cooking to trap steam.

Cooking time:

- 4–5 minutes per side over very low heat (about 140–150°C / 285–300°F).

Tip:

Don’t rush. The key to the jiggle is slow cooking and a very airy batter. I usually use two spatulas to flip them carefully without collapsing.

Fluffy Vegan Pancakes Even Non-Vegans Will Love

You don’t need eggs or dairy to make pancakes that are thick, fluffy, and delicious!

Ingredients swaps:

- Plant-based milk: almond, oat, or soy milk — 300ml

- Egg replacement:

- 1 tablespoon (7g) ground flaxseed + 3 tablespoons (45ml) water (let sit 5 minutes to form a “flax egg”)

- Butter replacement:

- 2 tablespoons (30g) coconut oil or vegan butter, melted

Preparation tips:

- Follow the classic method exactly.

- Vegan batters are often slightly thicker — add an extra splash of milk if needed for easy pouring.

- Cook over medium heat as usual, but be a little more gentle when flipping, since egg-free pancakes can be slightly more delicate.

Personal experience:

I’ve served these vegan pancakes at community events and brunches, and nobody ever guessed they were plant-based!

Gluten-Free Pancakes That Taste Like the Real Thing

Going gluten-free doesn’t mean giving up fluffy, tender pancakes. You just need the right flour mix.

Ingredient adjustments:

- Gluten-free all-purpose flour blend — 200g (1 ½ cups) (Look for blends that include xanthan gum, which helps bind the batter.)

- Slightly increase the milk to 320ml (1 1/3 cups) because gluten-free flours absorb more liquid.

Key techniques:

- Mix gently but thoroughly — gluten-free batters can sometimes clump.

- Let the batter rest for 15 minutes instead of 10.

This gives the flour time to fully hydrate and improves texture.

Cooking tips:

- Medium-low heat works better for gluten-free pancakes — about 160–165°C (320–330°F).

- Cook a little longer on each side — about 3 minutes first side, 2–3 minutes second side.

Chef’s note:

When I’m making gluten-free pancakes, I often add a touch of cinnamon or vanilla to round out the flavor even more — it’s a small step that makes a big difference!

Pancakes from Around the World: A Tasty Journey

Pancakes aren’t just a classic in America — they’re loved and reimagined all around the world.

Each country brings its own twist, its own traditions, and its own flavors to the simple idea of a cooked batter.

Here are three pancake styles from around the globe that every home cook should try.

French Crêpes – Thin, Elegant, and Impossible to Resist

Crêpes are the sophisticated cousins of American pancakes — thin, delicate, and versatile.

They can be sweet or savory, rolled or folded, and filled with just about anything you can dream up.

Basic Sweet Crêpe Batter:

- All-purpose flour – 125g (1 cup)

- Whole milk – 300ml (1 ¼ cups)

- Large eggs – 2

- Butter, melted – 30g (2 tablespoons)

- Sugar – 1 tablespoon (optional, for sweet crêpes)

- Vanilla extract – 1 teaspoon (optional)

- Salt – a pinch

Preparation:

- Whisk together flour, eggs, and about half the milk until smooth.

- Gradually add the rest of the milk, melted butter, and optional sugar/vanilla.

- Rest the batter for at least 30 minutes at room temperature.

(This relaxes the gluten and prevents tearing.) - Heat a non-stick skillet over medium heat, lightly butter it.

- Pour about 60ml (¼ cup) of batter into the pan, swirling to coat it thinly.

- Cook for 1–2 minutes until the edges lift, flip, and cook another 30–60 seconds.

Chef’s tip:

The first crêpe usually isn’t perfect — it’s your “tester” to adjust pan temperature and batter thickness.

Favorite fillings? Nutella and strawberries, lemon and sugar, or ham and cheese if you’re going savory!

Russian Blini – 3 Classic Recipes You Must Try

Blini are a beloved part of Russian and Eastern European cuisine — smaller, slightly thicker than crêpes, and traditionally enjoyed with both sweet and savory toppings.

Here are three classic blini styles:

1. Traditional Yeast-Raised Blini

- All-purpose flour – 250g (2 cups)

- Whole milk – 400ml (1 2/3 cups), warm (about 40°C / 105°F)

- Active dry yeast – 1 teaspoon (4g)

- Eggs – 2

- Butter, melted – 30g (2 tablespoons)

- Salt – ½ teaspoon

- Sugar – 1 tablespoon

Steps:

- Activate yeast in warm milk with a pinch of sugar (5–10 minutes).

- Mix with flour, eggs, butter, sugar, and salt.

- Let the batter rise for about 1 hour in a warm place.

- Cook on medium heat with a lightly greased pan, using about 2 tablespoons of batter per blin.

2. Quick Blini (No Yeast)

- Use baking powder (2 teaspoons) instead of yeast.

- No rising time needed — you can cook immediately.

- Slightly thicker and perfect for a faster brunch.

3. Buckwheat Blini

- Replace half the flour (125g) with buckwheat flour.

- Adds a rich, nutty flavor — fantastic for savory toppings like smoked salmon or sour cream.

Serving ideas:

Caviar and sour cream for traditional style, or sweetened condensed milk if you have a sweet tooth.

Swedish Pancakes – Light, Sweet, and Perfect for Any Time

Swedish pancakes (Pannkakor) are like a cross between American pancakes and French crêpes — thinner than pancakes, but softer and eggier than crêpes.

Basic Swedish Pancake Batter:

- All-purpose flour – 120g (scant 1 cup)

- Whole milk – 300ml (1 ¼ cups)

- Eggs – 3 large

- Butter, melted – 30g (2 tablespoons)

- Sugar – 1 tablespoon

- Salt – a pinch

Preparation:

- Whisk eggs, sugar, and salt until light.

- Gradually whisk in flour and milk, alternating a little at a time to avoid lumps.

- Stir in melted butter.

- Rest the batter for 20–30 minutes.

- Cook with minimal butter over medium heat, using about 60–80ml (¼–⅓ cup) of batter per pancake.

- Flip once the surface is dry and the edges are lightly golden.

How I love to serve them:

With lingonberry jam and a dusting of powdered sugar — simple, sweet, and so good with a cup of coffee.

Ultimate Toppings and Fillings for Your Pancakes

Pancakes are amazing on their own — but the real magic happens when you pile on toppings or tuck delicious fillings inside.

Whether you’re a “classic syrup” person or the type who loads pancakes with bacon and cheese, there’s a perfect topping (or three) waiting for you.

Here’s how to take your pancakes from good to unforgettable.

Classic Sweet Pancake Toppings That Never Get Old

Sometimes, you just can’t beat the classics. These toppings have been loved for generations — and for good reason.

1. Maple Syrup and Butter

- How to use:

Warm real maple syrup slightly before pouring — it soaks in better. Add a small cube of butter on top to melt right into the pancake stack. - Pro tip:

Grade A Amber maple syrup has the richest flavor for pancakes.

2. Fresh Berries and Whipped Cream

- Best choices:

Strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries. - Serving idea:

Toss the berries with a teaspoon of sugar and let them sit for 10 minutes to make a natural syrup.

3. Nutella and Bananas

- How to use:

Spread a thin layer of Nutella between pancakes, add slices of ripe banana, then drizzle a little extra Nutella on top.

4. Honey and Greek Yogurt

- Fresh combo:

Spoon thick Greek yogurt over pancakes and drizzle with good-quality honey for a lighter, slightly tangy topping.

5. Cinnamon Sugar

- Simple but magical:

Mix 2 tablespoons sugar with 1 teaspoon cinnamon. Sprinkle generously over hot pancakes with a little melted butter.

Savory Pancakes: Cheese, Bacon, and Everything Better

Pancakes aren’t just for sweet breakfasts — savory pancakes are perfect for brunch, lunch, or even dinner!

1. Cheese-Stuffed Pancakes

- How to do it:

Add thin slices of cheese (like mozzarella, cheddar, or Swiss) between two small scoops of batter on the pan.

The batter seals around the cheese as it cooks — gooey, melty magic inside.

2. Crispy Bacon Pancakes

- Two options:

- Place cooked bacon strips directly onto the uncooked side of the pancake after pouring the batter.

- Or chop cooked bacon into bits and mix into the batter itself.

3. Smoked Salmon and Cream Cheese

- Serving idea:

Spread cream cheese on the pancake, layer thin slices of smoked salmon, and sprinkle with chopped chives. Perfect for a more elegant brunch.

4. Herb and Garlic Pancakes

- How to flavor the batter:

Add 1 tablespoon chopped fresh herbs (like parsley, dill, or chives) and a pinch of garlic powder into your pancake batter before cooking.

Homemade Syrups and Sauces to Elevate Your Pancakes

Want to seriously upgrade your pancake game? Homemade syrups and sauces are easier than you think — and 10× more delicious than store-bought.

1. Simple Berry Sauce

- Ingredients:

200g mixed berries (fresh or frozen), 2 tablespoons sugar, 1 tablespoon lemon juice. - Instructions:

Simmer everything together over medium heat for 5–7 minutes, until the berries burst and the sauce thickens slightly.

2. Chocolate Ganache Drizzle

- Ingredients:

100g dark chocolate, 100ml heavy cream. - Instructions:

Heat the cream until just steaming, pour over chopped chocolate, let sit for 1 minute, then stir until smooth.

Drizzle warm over pancakes — it’s rich, decadent, and irresistible.

3. Homemade Salted Caramel Sauce

- Ingredients:

200g sugar, 90g butter, 120ml heavy cream, pinch of sea salt. - Instructions:

- Melt sugar in a saucepan over medium heat until golden.

- Stir in butter carefully.

- Add cream slowly while stirring (it will bubble a lot).

- Stir in salt and cool slightly before using.

Quick tip from my kitchen:

“Keep a little jar of homemade berry sauce or caramel in the fridge — pancakes (or even plain toast) instantly become a special treat.”

Expert Tips for Pancake Success

After flipping literally thousands of pancakes (some more successful than others), I’ve learned that small details make a big difference.

Here are my best insider tips to help you nail perfect pancakes every single time.

5 Common Pancake Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

1. Overmixing the Batter

- The mistake: Stirring the batter until completely smooth.

- The fix: Stop mixing as soon as the flour disappears. A few lumps are good! They keep the pancakes tender and fluffy.

2. Using a Pan That’s Too Hot

- The mistake: Turning the heat high to cook faster.

- The fix: Keep your pan at medium heat, about 175°C (350°F). Pancakes need time to cook through without burning.

3. Flipping Too Early (or Too Late)

- The mistake: Flipping before the edges are set, or waiting too long and drying them out.

- The fix: Flip when you see bubbles form and pop on the surface, and the edges look dry — usually after 2–3 minutes.

4. Pressing Down After Flipping

- The mistake: Flattening the pancake with the spatula.

- The fix: Let them cook naturally! Pressing pushes out air and ruins the fluff.

5. Skipping the Resting Time

- The mistake: Cooking immediately after mixing.

- The fix: Rest your batter for 10–15 minutes. It relaxes gluten and activates baking powder for better rise.

How to Keep Pancakes Warm and Fluffy Until Serving

Pancakes are best fresh, but if you’re making a big batch for a crowd, here’s how to keep them warm without drying them out:

1. Use a low oven:

- Preheat your oven to 90–100°C (200–215°F).

- Place a wire rack over a baking sheet (this keeps the bottoms from getting soggy).

- As you finish each pancake, transfer it onto the rack in the oven.

2. Cover loosely with foil:

- Tent foil over the pancakes to trap a little moisture but not steam them into mush.

3. Don’t stack right away:

- Stacking immediately traps steam and makes the lower pancakes soggy.

Keep them in a single layer as much as possible until serving.

How to Store Pancakes and Reheat Them Without Drying Out

Got leftovers? Lucky you — pancakes reheat beautifully if you do it right.

How to Store:

- Let pancakes cool completely on a wire rack.

- Stack with a small piece of parchment paper between each pancake.

- Store in an airtight container or a zip-top bag.

- Refrigerate for up to 3 days or freeze for up to 2 months.

How to Reheat:

For refrigerated pancakes:

- Oven: Preheat to 180°C (350°F). Cover pancakes with foil and heat for 5–7 minutes.

- Microwave: Wrap 2–3 pancakes in a damp paper towel. Microwave for 20–30 seconds at medium power.

For frozen pancakes:

- Thaw overnight in the fridge if possible.

- Reheat using the same methods above.

- Or pop them straight from freezer to toaster for a crispier edge!

Chef’s tip:

Sprinkle a tiny bit of water on each pancake before microwaving — it creates steam and keeps them from drying out.

Special Occasion Pancakes That Wow

Pancakes aren’t just an everyday breakfast — they can also be the centerpiece of special celebrations!

Whether it’s a traditional feast or a fun family morning, pancakes bring an extra bit of joy when you give them a festive twist.

Here’s how to make your pancakes unforgettable for any occasion.

Pancakes for Shrove Tuesday: Traditions and Tips

Shrove Tuesday — also known as Pancake Day — is a centuries-old tradition where people used up rich ingredients like eggs, butter, and milk before Lent. And what better way to do that than with a big stack of delicious pancakes?

Classic Shrove Tuesday Pancakes:

- Closer to French crêpes than thick American pancakes.

- Batter: 125g (1 cup) flour, 300ml (1 ¼ cups) milk, 2 large eggs, pinch of salt.

- No baking powder needed — these are meant to be thin!

Serving ideas:

- A sprinkle of sugar and a squeeze of fresh lemon juice — the traditional British way.

- Fruit preserves, chocolate spread, or simply powdered sugar.

Pro tip:

Organize a pancake race! (Yes, it’s a real tradition!) Participants race while flipping pancakes in a pan — it’s messy, hilarious, and a guaranteed memory-maker.

Festive Pancake Ideas for Christmas, Easter, and More

Pancakes are a blank canvas for every holiday — just a few creative touches can make breakfast feel magical.

Christmas Pancakes:

- Spiced Pancakes: Add 1 teaspoon cinnamon, ¼ teaspoon nutmeg, and a pinch of cloves to your batter.

- Decorate: Top with whipped cream “snow,” red berries, and green sprinkles for a holiday look.

Easter Pancakes:

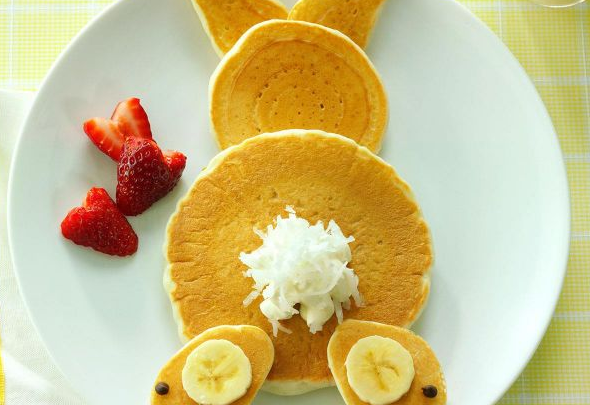

- Pastel Pancakes: Divide batter into three bowls and tint with natural food coloring (pink, yellow, light green).

- Decorate: Shape into bunny faces using banana slices for ears and blueberries for eyes.

Birthday or Celebration Pancakes:

- Confetti Pancakes: Stir rainbow sprinkles into the batter right before cooking.

- Serving idea: Stack them high, add candles, and serve instead of cake!

Chef’s tip:

Always keep a few little extras — whipped cream, colorful sprinkles, chocolate chips — on hand. They instantly turn a simple breakfast into a party.

Pancake Art for Kids: Easy Designs and Big Smiles

Making pancake art is one of the easiest (and messiest!) ways to get kids excited about breakfast.

Basic tools you’ll need:

- Squeeze bottles (like ketchup bottles) filled with pancake batter.

- Food-safe coloring if you want to make different colors.

- A non-stick griddle.

Easy design ideas:

- Smiley faces: Draw two dots for eyes and a big curved line for the smile.

- Animal shapes: Bunnies, cats, or bears are simple to create with just a few circles.

- Letters and numbers: Great for birthdays or learning activities.

Pro tips for pancake art:

- Draw the outline first and let it cook for 10–15 seconds before filling it in. This gives definition to the shapes.

- Keep the heat low (around 150°C / 300°F) — art pancakes cook slower than regular ones.

Personal favorite:

Making “breakfast dinosaurs” was always a huge hit when my nephews visited — even if my T-Rex looked more like a chicken half the time!

Low-Calorie Pancakes for Healthy Eating

Looking for a lighter way to enjoy pancakes without the guilt?

You’re in the right place.

Over the years, I’ve tested and perfected a handful of low-calorie pancake recipes that don’t just save you calories — they actually taste amazing.

These recipes use simple swaps like oat flour, Greek yogurt, and egg whites to keep pancakes fluffy, flavorful, and full of goodness.

Whether you’re counting macros, eating clean, or just looking for healthier breakfast ideas, these five pancake recipes are designed to fit right into your lifestyle — no weird ingredients, no bland flavors, and absolutely no compromise on joy.

Low-Calorie Pancakes for Healthy Eating: 5 Tried-and-True Recipes

Just because you’re eating healthy doesn’t mean you have to give up pancakes.

With a few smart ingredient swaps — and the right techniques — you can make pancakes that are low in calories, packed with protein or fiber, and still taste absolutely delicious.

Here are five of my favorite low-calorie pancake recipes, tested and tweaked over the years in my kitchen.

1. Oatmeal Banana Pancakes

If you’re looking for a naturally sweet pancake with simple ingredients, this is the one.

Banana adds moisture and flavor, and oat flour keeps the texture soft and satisfying.

Ingredients (makes 6 small pancakes):

- 100g oat flour (about 1 cup)

- 1 medium ripe banana (about 120g)

- 1 large egg

- 150ml low-fat milk or almond milk (⅔ cup)

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoon cinnamon

- Pinch of salt

Preparation:

- Mash the banana until smooth.

- In a bowl, whisk together the banana, egg, and milk.

- Stir in oat flour, baking powder, cinnamon, and salt.

- Rest the batter for 5–10 minutes.

- Cook over medium heat on a non-stick pan, about 2–3 minutes per side.

My tip:

If the batter looks too thick (depending on the banana’s size), add a splash more milk.

| Nutritional Info (per pancake) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Calories | 85 kcal |

| Protein | 3 g |

| Fat | 2 g |

| Carbs | 13 g |

2. Greek Yogurt Protein Pancakes

These are my go-to when I need a high-protein breakfast that feels like a treat.

Greek yogurt keeps them moist and adds a slight tang, almost like cheesecake pancakes.

Ingredients (makes 4 medium pancakes):

- 150g non-fat Greek yogurt (about ½ cup + 2 tbsp)

- 1 large egg

- 50g oat flour (about ½ cup)

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoon vanilla extract

- Optional: Sweetener of choice

Preparation:

- Whisk yogurt and egg together until smooth.

- Add oat flour, baking powder, vanilla, and sweetener if using.

- Let batter rest for 5 minutes.

- Cook low and slow to let the pancakes puff up beautifully.

Chef’s advice:

Use thick Greek yogurt — if it’s too runny, your pancakes might spread too much.

| Nutritional Info (per pancake) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Calories | 90 kcal |

| Protein | 7 g |

| Fat | 2 g |

| Carbs | 9 g |

3. Cottage Cheese High-Protein Pancakes

When I’m helping someone build a muscle-friendly breakfast, I always suggest these.

Cottage cheese adds serious protein and keeps the pancakes light and moist.

Ingredients (makes 5 small pancakes):

- 150g low-fat cottage cheese

- 2 large eggs

- 30g oat flour (¼ cup)

- ½ teaspoon baking powder

- Pinch of salt

Preparation:

- Blend all ingredients together for a smooth batter.

- Rest for 5 minutes.

- Cook over medium heat, 2–3 minutes per side.

Pro tip:

Use small curd cottage cheese for best texture — and don’t skip blending, or the batter will be too lumpy.

| Nutritional Info (per pancake) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Calories | 75 kcal |

| Protein | 7 g |

| Fat | 3 g |

| Carbs | 4 g |

4. Almond Flour Keto Pancakes

These are perfect for low-carb eaters or anyone following a keto lifestyle.

They’re rich, satisfying, and surprisingly easy to flip!

Ingredients (makes 4 small pancakes):

- 100g almond flour (about 1 cup)

- 2 large eggs

- 60ml almond milk (¼ cup)

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ½ teaspoon vanilla extract

- Pinch of salt

Preparation:

- Mix all ingredients until combined.

- Let batter rest 5–10 minutes (almond flour needs time to hydrate).

- Cook on medium-low heat — they brown faster than regular pancakes.

Personal experience:

Be gentle when flipping — almond flour pancakes are a little more delicate but taste incredibly buttery and soft.

| Nutritional Info (per pancake) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Calories | 120 kcal |

| Protein | 5 g |

| Fat | 10 g |

| Carbs | 3 g |

5. Egg White Fluffy Pancakes

These are super low-calorie and light, perfect when you want a big stack without the guilt.

Ingredients (makes 6 pancakes):

- 4 large egg whites

- 60g oat flour (about ½ cup)

- 100ml unsweetened almond milk (about ⅓ cup + 1 tbsp)

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- Pinch of salt

- Sweetener and vanilla extract (optional)

Preparation:

- Whisk egg whites to soft peaks.

- Mix flour, baking powder, and salt separately.

- Gently fold the dry mix into the whipped egg whites, adding milk slowly.

- Cook immediately on medium-low heat.

Advice:

Don’t overfold! The air in the egg whites is what gives you incredible height with almost no calories.

| Nutritional Info (per pancake) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Calories | 55 kcal |

| Protein | 5 g |

| Fat | 1 g |

| Carbs | 6 g |

Final Thoughts

“Healthy pancakes don’t have to taste like cardboard.

When you balance the ingredients right and use a little technique, you can enjoy fluffy, flavorful pancakes — and still stay on track with your goals.”

Pancake FAQs: Your Top Questions Answered

Because you’re overmixing the batter! Stir only until the dry ingredients disappear. A few lumps are fine — overmixing develops gluten, which makes pancakes dense instead of fluffy.

Your batter is too runny. Try adding 1–2 tablespoons more flour. The batter should be thick enough to hold its shape for a moment before it spreads.

The pan is too hot. Pancakes need medium heat (around 175°C / 350°F) to cook through slowly without burning on the outside.

You can, but the pancakes will be less rich and flavorful. Milk adds fat, which gives better taste and a softer texture. If needed, use half water, half milk.

Watch for bubbles that form and pop on the surface, and for the edges to look dry. That’s your perfect flip signal — usually around 2–3 minutes.

You’re probably skipping salt or using too little sugar. Even sweet pancakes need a little salt to bring out flavor, and just a touch of sugar improves browning.

Lightly, yes! Wipe the pan with a paper towel dipped in butter or oil between pancakes to prevent sticking and keep that golden color.

Like heavy cream or thin yogurt — it should pour slowly but not run like water. If it’s too thick, add a tablespoon of milk; too thin, a tablespoon of flour.

Yes, but leave out the baking powder and add it fresh in the morning for best fluffiness. Otherwise, the batter can lose its rise.

Place cooked pancakes on a wire rack in a 90°C (200°F) oven, loosely tented with foil. This keeps them warm without steaming them soggy.

A non-stick skillet or a well-seasoned cast-iron pan works best. Flat, heavy-bottomed pans distribute heat evenly and prevent hotspots.

Rest the batter for 10–15 minutes after mixing. This relaxes gluten and activates the baking powder, making your pancakes fluffier.

Absolutely! Stack cooled pancakes with parchment paper between them, seal in a bag or container, and freeze for up to 2 months.

For best results, reheat pancakes in the oven at 180°C (350°F) covered with foil for 5–7 minutes. Or pop them in the toaster for crispier edges!

Yes! Replace the egg with a flax egg (1 tbsp ground flaxseed + 3 tbsp water) and use plant milk. Vegan pancakes can be just as fluffy and delicious.

The pan might not be hot enough, or it’s not properly greased. Always preheat your pan and lightly grease it before adding batter.

Separate the egg, beat the white to soft peaks, and gently fold it into the batter. It adds extra air and lift for cloud-like pancakes.

About 60ml (¼ cup) per pancake is perfect for even cooking and easy flipping.

Try vanilla extract, lemon zest, cinnamon, nutmeg, or even a splash of buttermilk. Little tweaks can turn basic pancakes into something amazing.

The first pancake is always a tester! Use it to adjust your heat and grease level. After the first one, the pan settles and pancakes come out perfect.